PRI's The World aired a story (3/31/09) about the Cambodian Tribunal on the 1970s politicide* at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. The reporter described the admission of guilt and what appears to be sincere contrition shown by the man in the dock, Kaing Guek Eav, aka Comrade Duch. Duch was infamous for his role as a head of Pol Pot's S-21 torture facility; now he is a born-again Christian who seeks forgiveness.

The dynamics of transitional justice and war crimes tribunals have been of (an academic) interest to me for some time, but it's a hard thing to wrap your head around. How does a society recover from a historical tragedy? It's one thing to demonize and ostracize an invading army or individual enemies of the state, but when a good deal of your society is complicit in some way, how is that rift healed? This is obviously a big question, and I'll take this post to pose a couple questions and see if I can lay out what the literature says about it in a few subsequent posts.

No doubt there are plenty Cambodians who had been waiting quite some time to see the day this tribunal would come. The Guardian managed to speak to a survivor of the camp who has a good deal of justifiable anger about what happened 30 years ago. But what is most interesting to me is how the sitting government is handling it. According to the reporter, many of the highest government officials in Cambodia are former Khmer Rouge. They would just as soon try the five defendants scheduled to come before the court, and get it over with without much fuss. The World also says that the tribunal has gotten no significant coverage in local media and that many are oblivious or just uninterested, to which the reporter asks (and I'll paraphrase here, until I can get a transcript): if a tribunal tries and convicts a former mass-murderer of crimes against humanity and nobody notices, does it even matter?

This question gets to the heart of the matter. Let's break this down really quick: One of the essential functions that a state provides is to establish order, generally in the form of written law, and to deal out justice to those who break the codes of the order that has been established. I take a functional perspective on this**: Societies achieve a consensus on what the order should be, and institutions of justice provide a means through which order can be restored after it is breached. So long as those who have breached the order are a very small part of society, they can be either removed from society (life imprisonment, capital punishment, ostracism) or brought back into society after undergoing certain ordeals (demonstrations of penitence, punishment, rehabilitation, etc.). The problem is, if enough people are complicit, something of an entirely different kind (and magnitude) is necessary. Hence war crimes tribunals, transitional justice and national processes of reconciliation.

But, considering the kind of task they do, it's not clear if the analogy between conventional justice and transitional justice of this kind is a perfect one. How are there goals different? What exactly do they accomplish? Do they change anyone's minds about the past? Do they provide catharsis to those who were wronged? What are the stakes to the victimizers and how should they be treated? To what extent is forgiveness possible (or desirable) with those who were members of the Khmer Rouge? If these trials come 30 years after the fact, is it still relevant to the present day society?

Most interestingly, to my mind: what about the reporter's question above? If it is in deed true that the majority of the people of Cambodia are oblivious to what's going on, is it possible that a potential goal of societal catharsis is not possible? What is the role of the public at large in a process like this?

I feel compelled to say that I fully support the work of tribunals like the one in Cambodia, but I ask these questions as someone making an attempt to approach the issue objectively: taking as a given that these tribunals happen, what are the desired effects and what are the actual outcomes?

More posts to come, but let me know what you think so far.

* I go with Ted Gurr's definition, because I don't think 'genocide' applies to this case, but that's kind of splitting hairs

** I will, right now, admit my utter ignorance of other approaches to this. I'm positive there are plenty of perspectives in the world of legal theory and philosophy, but I'm not familiar with them.

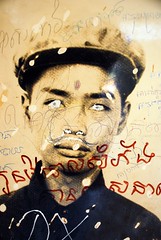

photo: flickr/lecercle